This summer, I have been searching for opportunities to volunteer with various wildlife agencies to gain some practical experience in the realm of wildlife conservation. One of the projects I signed up for was the Slate Lakes Grassland Restoration which the Arizona Elk Society spearheaded. The project would take place during the 3rd week of July roughly 30 miles northwest of Flagstaff. My Dad and I packed and left our home in New River on the 17th to set up camp. Arriving at the AES camp late for dinner, we were immediately greeted by a friendly outdoorsman who offered us from brats, buns, and condiments. He proceeded to rush around excitedly to make our dinner as convenient as possible. After exchanging names and handshakes, we ate our dinner and looked for a good spot to set up camp. We could faintly discern the shapes of RVs, trucks, and tents in the dark as we drove around the perimeter of the small forest which the AES base camp encircled. Before crawling into my sleeping bag for the night, I decided to study the local insect life.

|

| Callistege intercalaris |

|

| An Emerald moth - probably Nemoria obliqua |

After some good arthropodic discoveries, I decided to get some sleep; we had a long day ahead of us.

I could hear the wind rushing through the pines and the swallows calling when I woke in the morning. My Father and I enjoyed a hearty breakfast of biscuits and gravy which was generously provided by the AES. We also had some opportunities to talk with fellow outdoorsmen and elk enthusiasts. I was blessed with a chance to speak with the Arizona Elk Society's Executive Director, Steve Clark after breakfast. I was hoping he would sign my volunteer service record sheet. He not only did that for me, but also asked me to take photos on behalf of the AES and write an article about the event for their magazine! I was very excited for the responsibility. Birdwise, I recorded 24 species at our base camp. Among the most notable were a Dusky Flycatcher, Mountain Chickadee, Painted Redstart, and a pair of Red Crossbills.

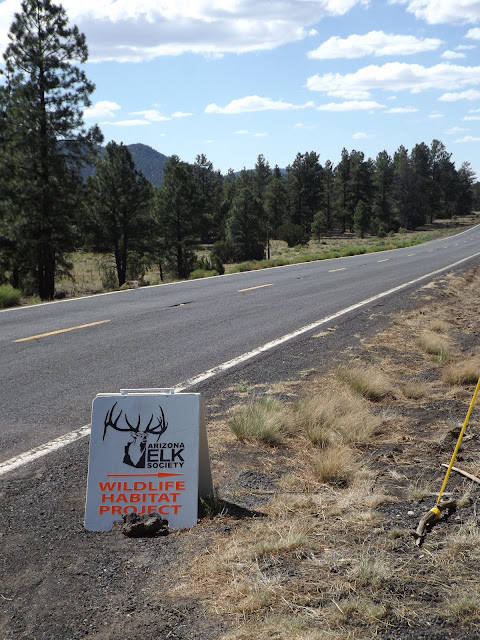

After a well-executed safety briefing, we departed for the project site. The mission was simple - cut the branches of small pines and junipers with hand tools so the trained sawyers could remove the trees completely. This would open up tracts of former grassland which would help improve the habitat to better suit the needs of migratory Pronghorn and Elk. When we were nearing the project site, a cow Elk sprang out from cover and sprinted across the clearing; a clear reminder of why we were here.

The team gathered together for some guidance from a Forest Service biologist before embarking on the project. My dad and I tag-teamed the large junipers and let everyone else deal with the simple and easy-to-cut pines. The juniper's branches were tough and woody, much unlike the soft and resinous nature of a pine branch. Because the junipers were quite tall, we were unable to cut all of their branches. Instead, we cleared everything away from the trunk in order for the sawyers to have easy access to the base of the tree. While clearing branches from our work site, I flushed a horned lizard from its hideout under a cactus!

|

| A female Greater Short-Horned Lizard |

Strangely, I noticed very few bird species in the area. My eBird checklist for the 6 hours and 50 minutes we were at the project site had only 5 species; a Broad-tailed Hummingbird, Common Raven, 2 Western Bluebirds, 3 Chipping Sparrows, and 2 Dark-eyed Juncos. I didn't feel at all bad that we were cutting trees - the birds barely seemed to use them anyway! After clearing the bases of several more junipers, my Dad and I were pretty wiped out. We decided to join the other volunteers who were 100 yards past us and chopping away.

|

| One of the sawyers felling a young pine whose branches have been cleared. |

After our lunch break, I worked alongside a Forest Service biologist and her team. One of the team members, a Puerto Rican-American, engaged me in conversation. He too loves birds and he has experience working with Mountain Trogons in Mexico and has also mist-netted birds in Venezuela. By 3 pm, the sawyers had advanced notably and we could hear the buzz of their chainsaws increasingly as we worked. When my dad and I left at 4 pm, the change we had made to the landscape was obvious. I could see the fruit of my labor. The land was opened up. A clear tree line could be distinguished. Grasses and forbs now had a chance to reclaim land that was once theirs. I know that Pronghorn and Elk will roam through this place once again.

While tearing down camp, I noted a few new birds for the trip; a Plumbeous Vireo, Steller's Jay, and some Lark Sparrows. As I was putting my tent in its bag, I heard a far off "Queeah" in the distance. It was a familiar sound, yet unfamiliar. Then it hit me. I had just heard my lifer Pinyon Jay calling! Unfortunately, I couldn't locate it, but there is no doubting a call as distinctive as the Pinyon Jay's. Although it wasn't a birding trip, I still got a lifer!

Godspeed and good birding to you all,

- Joshua